Creating the right environments to support fathers in the workplace isn’t just good for men, it’s good for the wellbeing of their families. It’s also a necessary step towards gender equality.

So why does uptake of parental leave for dads remain low? What is holding men back from taking their leave entitlement? We take a look at the barriers to parental leave affecting the participation rates of dads.

Earlier this year, the husband of tennis superstar Serena Williams wrote a widely shared essay for The New York Times that addressed an issue a lot of working dads struggle with silently: the desire to take paternity leave, even as overwhelming barriers keep them from doing so.

Alexis Ohanian (famous in his own right, as co-founder of Reddit) invited dads to ask their employers for paid leave: “Dads, let me be your air cover,” he wrote. “I took my full 16 weeks, and I’m still ambitious and care about my career. Talk to your bosses and tell them I sent you.”

Ohanian’s essay bluntly called out one of the biggest myths about working dads who want to take paternity leave—that they aren’t actually committed to work (spoiler: they are). It also cited some glaring statistics: in the United States, the only industrialised country that doesn’t guarantee paid family leave, only 9% of workplaces offer paid paternity leave. As a result, more than three quarters of dads go back to work within one week.

Paternity leave around the world

The state of paternity leave in other parts of the world isn’t much better. One report says that only 48% of countries provide paid paternity leave, and the time allotted is usually less than three weeks (and typically more like a few days). A 2016 study by RAND Corporation found that even in the EU, where the average length of paternity leave is 12.5 days, actual uptake of these more generous leave policies is low. In Australia, which offers paid leave for ‘primary carers’, mothers take 95% of this leave, and only one in 20 fathers take it.

Commentator Annabel Crabb, whose recent essay, Men at Work: Australia’s Parenthood Trap, is making the rounds in Australia, tweeted a graphic that captures the problem: it plots the hours men and women spend working, parenting, and doing household chores against the age of their youngest child. The working hours line for men is almost perfectly straight, hovering around 47 hours per week from the time the kid is born through to age 12. The working hours line for women drops off a cliff as soon as the child is born.

Crabb’s point is not just to show that having kids affects women’s employment (though it does), it’s to demonstrate that having kids has almost no impact on the dad’s employment (which it should). As Crabb writes: “Gone are the days when fathers were considered somehow an optional extra to the parenting process.”

So what’s keeping men from taking paternity leave, and why do guys like Alexis Ohanian believe more men should be taking it?

Why men aren’t taking paternity leave

There are lots of reasons men don’t take paternity leave, and these vary from country to country. The RAND study identified several reasons for low uptake in the EU, including the fact that not all dads are eligible, there’s a lack of flexibility in when dads can take leave, taxes sometimes disincentivise leave, and cultural norms make taking leave a challenge.

Broadly speaking, dads don’t take leave when policies prevent them from doing so, when there’s some sort of trade-off or financial hit for doing so, or when taking leave violates cultural traditions.

Conservative parental leave policy

Government and employer policies create one of the first barriers when it comes to eligibility for leave. In the United States, which provides only unpaid leave at the federal level, it’s more common for women to take leave where paid parental leave is accessible in certain states, cities, and territories.

Employer policies are beginning to evolve in the US, but the trend is still that mothers are given maternity leave while leave for dads is not available or provided for a much shorter duration. As noted above, leave in Australia is for ‘primary carers’, and the default is that this person is the mother. In the UK, paid paternity leave is limited to one or two weeks, though there is an option for eligible couples to take shared parental leave.

Gender pay gap and the financial hit to families

When dads do have the option of taking leave, many don’t because there’s a financial trade-off: a lot of paid leave plans don’t fully compensate lost wages, so when opposite-sex couples make the decision about who takes more leave, they may choose the spouse who earns less. Given gender pay gaps, that’s often the mother.

Cultural stereotypes and stigmas

Financial penalties also come from cultural stigmas that damage the reputation and earning potential of dads who take leave. According to research by the Harvard Business School, more male employees (35%) than female employees (23%) felt care responsibilities hurt their career. More men (40%) than women (25%) also strongly agreed that “caregivers are perceived to be less committed to their careers than non-caregivers”.

Another study, by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, found that when applying for new jobs, parents who had been out of work to look after kids were about half as likely to get an interview as those who were unemployed due to a layoff. In competitive job markets, the same study found that employers are least likely to hire fathers who are caring for children.

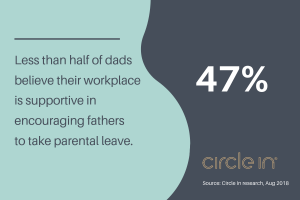

Circle In’s own research underscores these issues. In our survey of dads, less than half (47%) believed that their workplace was supportive in encouraging fathers to take parental leave. For those dads who said they hadn’t taken paid parental leave, the main barriers they cited were the demands of their job.

Paternity leave is good for dads, kids, and gender equality

Despite the low numbers of dads taking it, the case for paternity leave is strong.

One of the biggest benefits is the opportunity for dads to bond with their children. Studies have shown that paternity leave, especially longer leave, can help dads become more nurturing fathers and more supportive partners.

Paternity leave also supports gender equality—both at home and at work. Researchers have found that gender equality at home has stalled, even as progress has been made in the public spheres of work and politics.

Despite their increased workforce participation rate, women are still doing the bulk of unpaid household work and care. This means that women are doing more work than their peers were generations ago, when fewer women worked outside the home. Today, women are working at the office and then taking on a second shift at home. Mums also generally deal with a higher mental load, managing kids’ school and family schedules.

Gender dynamics at home are influenced by culture, and they are also imposed on families by government and workplace policies: since mothers are more likely to be given and to take maternity leave, they are also more likely to assume the role of primary caregiver. Since they’re at home anyway, they are also more likely to take on the role of primary chore-doer.

This changes when fathers in heterosexual couples take paternity leave: those dads spend more time parenting and doing household work than fathers who don’t take leave. This combats gender inequality at home and gives mums time to pursue their own career or personal ambitions or just chill out, which supports their physical and mental health. Men who take paternity leave are also supporting gender equality at work by giving their female partners the opportunity to more fully engage in their career.

There are also benefits to the couple when dads take paternity leave: It lowers a couple’s risk of divorce. And if the dad does assume more of the household duties, here’s another perk: gender equality at home is good for a couple’s sex life.

More dads want paternity leave

The good news is that a growing number of fathers are demanding parental leave.

One study, which surveyed dads in seven countries, found that 85% of fathers would be “willing to do anything to be very involved in the early weeks and months of caring for their newly born or adopted child”. A survey by the job site Indeed.com found that 44% of fathers were concerned about the amount of paternity leave they would get, and although the average new dad in the study said they received seven weeks of paternity leave (including paid and unpaid leave), they wanted 10 weeks. In the United States, 70% of all Americans—men and women—support paid paternity leave. This trend is likely to grow as new generations join the ranks of employees. Parental leave is especially important to Millennials.

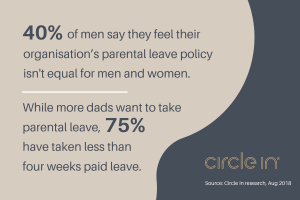

Our research backs this up. In Circle In’s survey of dads, 40% of men said they felt their organisation’s parental leave policy was not equal for men and women. More dads said they want to take parental leave, but three quarters of them said they had taken less than four weeks.

Let’s change the conversation

Parental leave is about parents—not just women. It’s time to move the discussion from ‘working mothers’ to ‘working parents’, and from ‘maternity leave’ or ‘paternity leave’ to ‘parental leave’.

Government and workplace policies need to be equally accessible to men and women, and other caregivers. Importantly, we also need to change the culture so that all working parents can take the time they need to bond with their kids, nurture their family, and support their personal and economic wellbeing.

To receive further insights into parental benefits and how organisations are supporting working parents, subscribe to our industry newsletter here.